Italian renaissance woodcut playing cards

The backs of the cards

Several of the sheet fragments contains unintended ink stains from

contact with other sheets before these were fully dried. Had this been

the case for just a single sheet, it could have been an accident – the

very reason that this particular sheet had not been used to produce

actual cards, but instead recycled for other purposes. As this occurs

very often, however, a much more probable reason is that these sheets

were discarded due to other defects, and immediately consigned to the

recycling bin

before drying, and thus staining the sheet

below.

There are two recognisable classes of such stains. One is mainly from

the red areas coloured in with stencils. This is the case for several

sheets from block C2 of the crude

pack.

However, on one of these sheets the black lines from the woodcut and one

other colour besides red is also present in a small area. This forms a

mirror image “contact copy” of the upper left corner of the queen of

swords from block T1 of the tarot pack, overlying

the intended design, and where it is strongest it is equally sharp and

distinct as that.

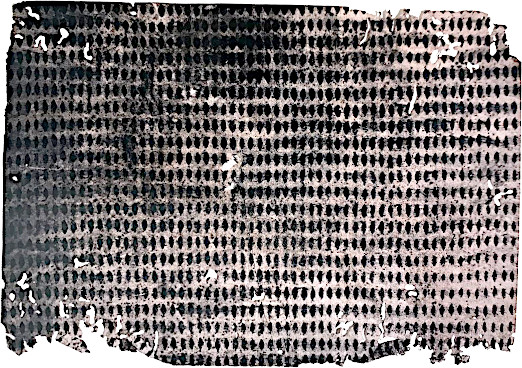

The other is mainly found on sheets from blocks T1, T2 and T3 from the tarot pack, and thus probably most closely

associated with this pack, but also on two sheets from block C1 from the “crude” pack. It is a checkerboard

pattern, rotated 45 degrees and elongated so that the spots are

lozenge-shaped. This can hardly be anything other than the cardback

design. The proportions are such that there are approximately 13 black

lozenges

both on the width and the length of the cards.

Further, it must be assumed that in the finished cards, the patterned cardbacks were folded around the edges of the card, so that a narrow strip containing more of the same pattern formed a frame covering the blank borders of each card. A single row of lozenges on one of the C1 fragments strongly supports this.

After making this conjecture, I have been informed that fragments of backing paper more or less matching this actually survives as uncut sheets as well. One unpublished example interestingly is the fifth fragment in the group otherwise containing fragments from the “mirrored” packs. Another does not have such a connection to these cards, but belongs to Albert Milano who published the account of those fragments, and is said to be quite similar.

As can be seen, this differs from my reconstruction in that the lozenges are slightly smaller, so that their tips do not quite meet; they are also slightly more elongated.

Another much less well preserved fragment that seems to have the same pattern is on the other hand closely connected to the family of card designs discussed here, as it survives in a group otherwise consisting of eleven fragments from the two Fournier blocks and one from an otherwise unknown block closely related to these and even more so the “mirrored” packs.